Municipalities must be vigilant in setting GHG reduction targets

Dr. Mir F. Ali

It seems to be a popularity context in the midst of some municipalities to set higher targets for reducing GHG emissions with the ambition to be recognized as a national or global leaders depending upon the size of their ego. There are two things appear to be profoundly wrong with this picture:

- Somebody forgot to tell those municipalities that setting up targets is important but only a small part of the overall scope of the initiative and rewards and awards are typically claimed based on how and when those targets were accomplished. More importantly, what was the costs of those reductions – were they justified by increasing taxes or charging more for the municipal services or imposing overwhelming restrictions on the developers/builders for building green in their jurisdictions, or boosting organizational effectiveness and efficiency of the municipalities or finally, a combination of all the above; and

- If elected municipal officials are taking the risk of setting or approving unrealistic targets for 2020 or 2050 only for the 15 minutes of limelight and assuming that they are not going to be there to face the drums, they need to think it over. They will be leaving behind a huge mess for the next generation to clean up and this can’t possibly be fair from any point of view.

The good news is that no other governments, but local governments (Municipalities), are directly responsible for their buildings and vehicle fleets. They can use this to influence the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in their jurisdictions as they are aware of the emissions and energy consuming capabilities of the buildings as well as transportation.

The real challenge is how they are going to do it.

Here is a Canadian perspective for reducing GHG emissions in Canada according to the document, Kyoto and Municipalities:

- Kyoto targets require Canada to reduce GHG emissions 6% below 1990 level by 2008-12;

- Canada’s GHG emissions in 1990 were 607 Megatonnes (Mt);

- Expected GHG emissions in 2010 estimated to be 809 Mt;

- Expected reduced GHG emissions in 2010 based on 6% below 1990 is estimated to be 571 Mt; and

- Therefore, the gap is about 240 Mt and is expected to be bigger - driven by economic and population growth.

Here is the Canadian strategy to reduce GHG emissions:

- Federal government’s Action Plan 2000 to reduce = 50MCarbon sinks = 24Mt;

- Emissions trading up to 144Mt;

- Credit for “cleaner energy exports” = 70Mt;

- Use of new technologies such as fuel cells; and

- Purchase of credits from Russia and Romania.

Here is the Province of British Columbia’s perspective for reducing GHG emissions within the Province:

- In support of the federal government’s plan for the reduction of GHG emissions, the 2007 Provincial enactment of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act (GGRTA) identified climate change as critically important. With British Columbia’s annual emissions exceeding 66 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, this legislation signalled a major step towards confronting the Province-wide contribution to global warming;

- Significantly, the GGRTA established specific targets mandating that total BC emissions be reduced by 33 percent by 2020 and 80 percent by 2050. The Province subsequently set interim targets of 6% reduction by 2012 and 18% by 2016 based on realistic and economically viable strategies; and

- Recognizing that 43% of emissions are under the influence of regional districts and municipalities, the Province requires that all local governments identify GHG reduction targets, policies, and plans in their Official Community Plans. In order to forward these efforts, the Province recently released draft Community Energy and Emissions Inventories (CEEIs) for all local governments in British Columbia.

Now it’s left entirely up to the municipalities to perform regardless of the following expected impacts and with very little or no federal or provincial financial incentives:

- More threats to already shaky business enterprises in communities;

- Reduced ability to maintain existing tax levies;

- Restraints on wages with indirect impacts on other businesses and municipal undertakings;

- Reduced revenues to higher levels of government and, in turn, reduced cash flows back to already constrained municipalities; and

- Reduced ability of local government to provide services.

It must be recognized that in order for the municipalities to make a commitment to reducing GHG emissions, they have to be convinced about what the leading climatologists like NASA’s Jim Hansen have said that the window for action is closing and that if we – as a species — do not make significant progress reversing GHG emissions trends within the next ten years, it will be too late to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Thus, it is time for action and the municipalities’ action plans must be deemed failures if they do not produce the rapid response that is needed to mitigate GHG emissions.

Coming back to municipalities setting GHG emission reduction targets, municipalities must understand that target setting has to be an integral part of a performance management mechanism which should be designed to manage GHG emissions reductions on a timely as well as cost-effective basis and it should not be viewed as a statistical or administrative process carried out by a few in isolation of the overall GHG emissions reduction planning policy.

Furthermore, targets are generally expressed as a percentage reduction from the emission inventory baseline year. Targets are used as a tool to help reduce GHG emissions. Targets must be time bound, they must define a ‘desired’, ‘promised’, ‘minimum’ or ‘aspirational’ level of reduction and they must be measured via performance indicators. By the way, aspirations are the ultimate and desired levels of performance. They are not always achievable but reflect the ambitions of the individual, team, service or authority. They might also be described as vision or mission when related to the broadest or most fundamental objective of the organisation or partnership. Other terms used might be aims or ambitions.

Another important point to keep in mind is that since targets are set as a percentage of the baseline year, plans for reducing emissions must account for any growth the community will experience between the baseline year and the target year. Therefore, growth should be one of the factors considered when attempting to set a reachable target.

Targets for reducing GHG emission can differ between community emissions and municipal operations emissions. Typically, municipalities often set more aggressive targets for their own operations simply because they have more direct control over their operations.

According to the Cities for Climate Protection (CCP) program, targets are generally established with input from citizens, non-profit and community groups, the private sector and municipal staff; typically, through the advisory committee. Council must approve the target and timeline for achieving it. Preferred targets are 20% reduction in GHGs from municipal operations and at least a 6% reduction from the community, both within 10 years of joining the program. This target was adopted by the City of Toronto in 1990 as the first GHG reduction target officially adopted by any government body. It has been the standard for participants in the CCP campaign ever since. Other common targets adopted by local governments include:

- A 10% reductions in emissions, within 10 to 15 years of the base year;

- The national Kyoto Protocol target for the country in which the jurisdiction in located; or

- No net greenhouse gas emissions – usually set as a target that drives continual improvement, or to make a strong political statement of commitment.

The target can and should be refined and the goal increased over time. Ultimately a 60% – 80% reduction in GHG emissions is needed to avert the impacts of climate change.

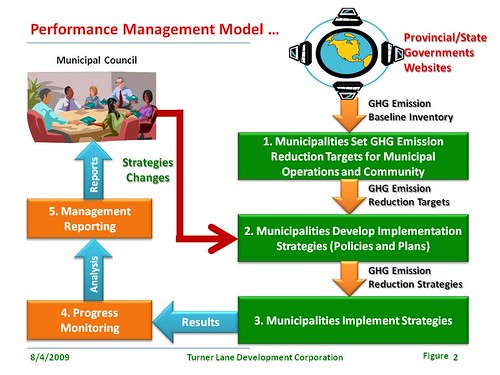

Here is a Performance Management Model which is designed to help municipalities manage their process of reducing GHG emissions in their jurisdictions:

Most of the provinces have already completed the baseline inventory of GHG emissions for their municipalities and those inventories are made available on their respective websites which is shown on the graph as a starting point. The majority of those inventories which are produced by various provinces indicate the energies consumed and GHG emissions emitted in a given year in a given municipality. GHG emissions in the inventories are divided into three categories: Buildings, On Road Transportation, and Community Solid Waste. The categories of Buildings and On Road Transportation are further divided into sub-categories. Here is a brief description of the graph (Figure 2), step by step:

- Setting Targets: Municipalities review their baseline GHG emissions inventories in order to understand the relationship between the amount of energies consumed and the amount of GHG emissions emitted in their jurisdictions. They also try to compare their inventories with the compatible neighbouring municipalities’ inventories to understand the reasons behind the obvious differences. Then they develop their own vision for reducing GHG emissions in their operations as well as in their communities which helps them to come up with some realistic numerical values for setting up their targets. Before they finalize their targets, municipalities make sure that their targets are realistic, practical, and achievable. Once their targets are finalized, they need to develop rules or performance indicators for measuring and monitoring the progress for each target;

- Developing Implementation Strategies: In this phase of the model, municipalities conduct a gap analysis, comparing their base inventories against their targets to determine the gap in that particular year. Once the gap is determined and defined, further analysis will be required to identify what is needed to be done to bridge the gap which will lead to the articulation of an action plan. In order to support the plan, necessary policies and guidelines will have to be developed by each municipality for their jurisdictions. Here is an opportunity for the municipalities to consider developing some complimentary strategies to minimize their operational overheads and maximize the performance of their resources which will help reduce the overall cost of the process;

- Implementing Strategies: The activities identified and proposed as an action plan in the previous phase, need to be executed step by step, following the policies and guidelines;

- Monitoring Progress: The progress needs to be monitored following the rules/performance indicators that were developed under the phase 1 of the model. Necessary analysis will be have to be conducted to explain the trends, progress or shortfalls based on the results; and

- Reporting: The report produced under this phase of the model will include recommendations to the council and as a result of those recommendations; the council will approve the changes or realignment of the strategies to overcome any shortfalls.

It has been proven again and again that no model, regardless of how carefully articulated, is going to function as intended unless an accountability framework is formulated, describing who is going to do what, when, where, why, and under whose leadership. Here are a couple of realities or challenges:

- Politicians seem to be the driving force for the green initiatives in almost all municipalities. This is the main reason we see municipal interest in green initiatives going up and down like a yo-yo. Interest depends upon who is elected to govern the jurisdictions; and

- Generally, the municipal coffers are not rich enough to offer politicians any reasonable compensation packages which will allow them to dedicate their full attention to the municipal affairs. Consequently, their day jobs, businesses, and trades take them away to different cities and in some cases different countries for an extended period of time which is also a major problem for the municipalities.

Here is another reality. If the chief executive officers/city managers don’t become directly accountable for the green initiatives in their municipalities and assume the leadership role while fostering, educating, and assisting elected officials to seek public support, municipalities will continue to struggle and green initiatives will continue to suffer.

The chief executive officers/city managers in each municipality have to be visionary enough to look at the bigger picture and realize that ultimately each municipality is going to be allowed to emit so many tonnes of GHG emission in the atmosphere each year. If any municipality failed to live up to those expectations and exceeded their allocated GHG quota, they will have no choice but to purchase carbon credits to justify the excess GHG emissions from those municipalities which were successful in emitting less GHG emissions than what they were allowed to. This could very well be translated into a big money windfall or headache depending upon the size of the excess or credit and the price of the carbon credits at that time. This is no different than what will be happening to the provinces/states and countries around the world.

This is indeed a strategic opportunity for the municipalities to excel by working towards transforming municipalities into exemplary jurisdictions.

Dr. Mir F. Ali is a Sustainability Analyst with Turner Lane Development Corporation, a real estate development company with the commitment to build sustainable communities in British Columbia, Canada (mir@turnerlane.com).

Comments